Where would EU living wage legislation have impact for workers?

Martin Curley, Policy & Research at Katalyst Initiative, explores which countries will benefit the most from the Good Clothes, Fair Pay proposal and how the proposal, combined with good data, can help create the long-sought-after ‘level playing field’ for living wages.

Katalyst Initiative’s recent paper Trade Realities explores trade relations between the EU and major garment exporting countries. It illuminates where EU-based initiatives – like Good Clothes Fair Pay – are likely to have the most impact. Trade data provides a useful way to estimate the size of the EU’s influence on the garment industry in different countries. While this data only allows us to analyse the flows of finished garments, many of the principles we discuss here are relevant for fabrics and raw materials as well.

Apart from the EU – which remains a significant garment exporter – more than 90% of the world’s garment exports are produced by what Katalyst Initiative refers to as ‘The Group of 30’ – a set of countries in Asia, Africa, the Americas and Eastern Europe which together produce most of the world’s exported garments. Figure 1 shows the Group of 30, and the percentage of global production they represented in 2019.

Figure 1: ‘Group of 30’ major garment exporters

Europe as the world’s largest garment importer

But where do these exported garments go? Which buying countries have the potential to influence business practices in these garment-producing countries? One important finding, which underscores the importance of efforts like Good Clothes Fair Pay, is that Europe still matters a great deal when it comes to global garment imports. As we see in the figure below, the EU is still the single largest importer of garments from the Group of 30 countries. The EU’s import volumes mean that EU policies to improve conditions in supply chains do indeed have the potential to make a real difference.

Figure 2: The major garment importers from the ‘Group of 30’ countries

Given the large volume of EU garment imports, it is fair to say that the EU also has a particular obligation to regulate the behavior of the garment brands that sell products into the market here. The treatment of workers and the environment by the global garment industry is very much driven by the needs and demands of the ‘lead firms in supply chains,’ i.e. brands and retailers. The behavioral norms in the industry – the failure to pay suppliers enough to support a living wage; the choice to source from countries that are hostile to independent trade unions; the reliance on excessive overtime to compensate for poor production planning; and purchasing practices seen during COVID-19 - are all methods of shifting risk onto suppliers and workers in other parts of the world. The industry has not seen significant improvement on these and related issues despite 25 years of voluntary, industry-led initiatives.

During that same time frame, regulatory structures did not kept up with the globalization of supply chains, creating the loopholes that allow brands based in Europe, the US and other wealthy countries to reap the benefits of low-cost production without any accountability for associated negative impacts on workers or the environment. We hope the early 2020s will mark a turning point, where the EU (and the US and other countries) finally start to regulate the behavior of brands so that the benefits they reap from globalization are paired with responsibility to workers and the environment. The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive is a step in that direction; the Good Clothes, Fair Pay proposal is an important step further.

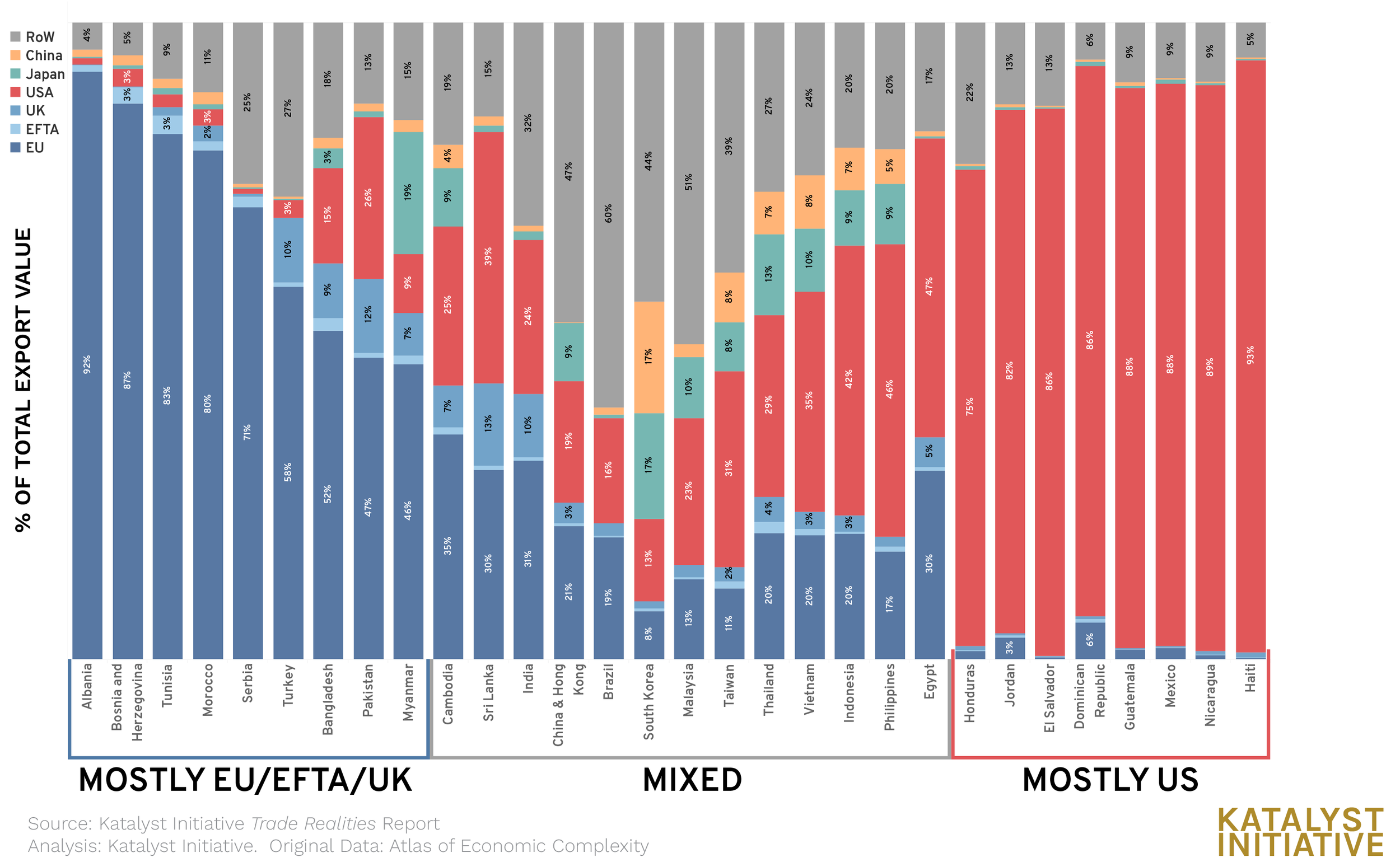

Europe’s import partners

As these and other proposals for laws, treaties and collective bargaining efforts aimed at supply chains develop, it will be important to understand how their impact may vary between garment-exporting countries. The figure below illustrates how much the EU imports from the Group of 30 countries. As we can see, there are basically three sets of countries: those where the EU is by far the largest trade partner; those with a mixed set of trade partners; and those from whom the EU buys almost nothing.

Figure 3: Garment exports from the ‘Group of 30’ to major importing economies

In the first group of countries (on the left hand side), the impact of the Good Clothes, Fair Pay proposal would be potentially transformative for the entire national garment industry. Anywhere from half to nearly all garment exports would be covered by living wage requirements.

In the second group of countries (in the middle of the graph), EU volumes are smaller, but still significant. And in several of these countries, the sheer size of the workforce means that potentially millions of garment workers would benefit.

In the third group of countries (on the right hand side) – where the US is the major trading partner – EU influence is minimal. But the combined, overall volumes of EU and US imports globally highlight the potential impact of a coordinated EU-US policy on living wages. The EU can do a lot on its own, and in many countries the EU alone can have a massive impact. Cooperation with the US could be transformative on a global scale.

Creating the level playing field

For more than 20 years, brands have resisted meaningful progress on living wages based on the shared supplier argument. The argument runs like this: garment brands almost never own or control their suppliers, and most garment factories make clothing for many different brands. Take, for example, a factory making shirts for 10 brands. 2 brands might be willing to pay enough to fund a living wage, but the other 8 are not. The 2 willing brands are unwilling to subsidize higher wages for the other 8 brands, so nothing happens. For a long time, brands have said what we really need is a ‘level playing field’ so that all competing brands were required to pay for living wages. The Good Clothes, Fair Pay proposal finally helps to create that level playing field, in several ways.

One practical impact of the proposal is to say: all brands who want to sell garments in the EU need to pay their suppliers enough to cover the cost of a living wage. There will no longer be a competitive advantage for any brands active in Europe to refuse to pay the costs of a living wage. The importance of creating a level playing field among brands in this manner cannot be understated.

But what about the shared supplier base? The trade data tells us that in countries where the EU is the major trade partner, the shared supplier base problem will no longer be much of a problem. If most of a country’s production is going to Europe, then most of that production will be held to the same living wage standards anyway.

In countries with more of a mixed export market, brands will need to make some choices. One option is to consolidate production into factories with other exporters to the EU. But many other options exist – for example lobbying export-country governments to raise legal minimums for all producers or lobbying the US, UK, Japan and other importing countries to match EU requirements – which would broaden the pool of factories where living wages were being paid.

There would be much to negotiate – with governments, with brands from other parts of the world, and especially with trade unions – to work out how to extend living wages to workers not producing goods for export to the EU. But we would argue that it is a far better negotiation to have than to maintain the status quo.